Blog

Rigoletto Review

Femi Elufowoju jr’s imaginative reinvention of Verdi's Rigoletto features some strong, compelling performances

Verdi: Rigoletto - Sir Willard White, Callum Thorpe, Eric Greene, Roman Arndt, Themba Mvula - Opera North (Photo Clive Barda)

Verdi Rigoletto; Eric Greene, Jasmine Habersham, Roman Arndt, dir: Femi Elofowoju jr, cond: Garry Walker; Opera North at the Grand Theatre Leeds

Reviewed by Robert Hugill on 4 Feburary 2022 Star rating: 4.5 (★★★★½)

Compelling performance bring Femi Elofowoju jr's remarkable contemporary re-invention of Rigolettoto life

Ostensibly, Victor Hugo’s play Le Roi s’amuse satirised the licentious court of King Francis I of France, but at the play’s 1832 premiere in Paris the authorities thought the subject close enough to home to ban it after one performance. Verdi’s opera Rigoletto uses the play as its source material, and he and librettist Francesco Maria Piave had similar problems when Rigoletto was premiered in Milan in 1851. Rigoletto should disturb and should hold a mirror up to society. But how to do so whilst dealing with the work’s misogyny and treatment of disability.

Femi Elufowoju jr’s new production of Verdi’s Rigoletto at Opera North (seen 4 February 2022 at the Grand Theatre, Leeds) takes a dramatic and remarkably compelling approach. Roman Arndt was the Duke with EricGreene as Rigoletto and Jasmine Habersham as Gilda, plus Sir Willard White as Monterone and Callum Thorpe as Sparafucile. Garry Walkerconducted, and designs were by Rae Smith.

Verdi: Rigoletto - Callum Thorpe, Alyona Abramova, Roman Arndt, Jasmine Habersham, Eric Greene - Opera North (Photo Clive Barda)

Elufowoju had moved the action to the present day with Arndt’s Duke as more of a high-end gangland boss, though the setting was unspecific. Smith’s stunning designs, with visuals channelling artists such as Kehinde Wiley and Yinka Shonobare, created their own strong atmosphere. Both scenes in Act One and that in Act Three were each like a picture, and each had a vivid use of colour.

But the production used colour in a different way as well. The casting was the opposite of colour blind and Elufowoju’s production placed race at its very centre. Having Rigoletto, Gilda, Monterone, Marullo and Countess Ceprano as people of colour in the largely white court of the Duke created a new setting that minded Elufowoju’s own background; he is British-Nigerian. Remarkably, this was his first opera production.

The problem with Rigoletto is that for the mechanics of the plot to work, Monterone’s curse on Rigoletto as to have dramatic immediacy (something Jonathan Miller did brilliantly in his English National Opera production). In the context of Elufowoju’s British-Nigerian background the curse does indeed work, and the production is very much about Rigoletto’s role as a black man in a modern and white society. Yet is all remains true to the original libretto.

Verdi: Rigoletto - Eric Greene, Jasmine Habersham

Opera North (Photo Clive Barda)

Elufowoju describes the setting thus, “We could be anywhere men mix power and wealth, and indulge in toxic misogyny in wanton abundance and abandonment. Abuse, corruption and criminal activity are rife, the world of the rich and mindless remains impenetrable”. Thus for Elufowoju, Rigoletto’s “’deformity’ is a manifestation of the paranoia of the outsider”.

In the title role, Eric Greene gave a remarkable performance, intense and very physical, alert to every nuance of the music, and he used his height to emphasise this. His wasn’t a likeable Rigoletto, and some moments in the first scene were positively nasty, and only in moments with his daughter did her unwind somewhat. There was a vividness to Greene’s performance which made you understand Rigoletto’s predicament. If Greene’s voice did not always respond to the pressure he put on it and lacked the idea amplitude for this role, this was more than compensated for by his musical intelligence and the compelling nature of his performance.

Jasmine Habersham made a charming Gilda, conveying her Miranda-like naivety and sense of wonder without ever making you think that she was dim, which is always a danger in this character. She has quite a light voice, perhaps lacking ideal amplitude, but true and she made her famous solo an interesting personal thought rather than simply a dazzling showpiece. She and Greene had a strong, believable relationship and their scene in Act One was a highlight. Gilda’s relationship with the Duke, or perhaps her idea of the Duke, was believable and in the second and third acts Habersham conveyed Gilda’s remarkable inner strength.

Roman Arndt’s Duke was a careless, charismatic character with great physical charm and an utter contempt for conventional morality, taking whatever he wanted. This was emphasised in he first scene as Elufowoju gave him a very present wife, a silent but present witness to his casual pursuit of other women. Arndt brought a nervous energy and great physicality to the role, and if his singing perhaps lacked an ideal Italianate sheen, it was vivid and musical. His fatal charm was demonstrable and believable.

Around these there were a series of strong performances, including five from members of the chorus. Sir Willard White was thrilling as Monterone, making the character’s two short scenes seem far more. His voice has lost none of its power and his attention to the text was exemplary. Callum Thorpe’s Sparafucile was present for the opening scene, and Thorpe combined wonderful blackness of voice with threatening sense of stillness that compelled both ear and eye. As his sister, Alyona Abramova made Maddalena much more than a vamp, bringing out her youth. Ross McInroy was a charming, selfish Ceprano with Molly Barker as his delightful wife. Thmeba Mvulla was Marullo, the only other black man at court, and he was fatally plausible. Hazel Croft made Giovanna a real character, not a cipher and Helen Evora was poised as the (female) PA-like page. Campbell Russell was Borsa, Gordon D Shaw was bodyguard and usher.

Verdi: Rigoletto - Eric Greene, Roman Arndt - Opera North (Photo Clive Barda)

As I have said, the settings were stunning, though the abstract visuals for Rigoletto’s house (including a full-sized zebra) threated to over-dominate the action. But the final inn scene, set in a liminal backstreet are complete with abandoned car, was something of a visual coup. The ending, with a dramatically vivid quartet and Rigoletto’s moving duet with his dying daughter, managed to be fresh and moving rather than hackneyed.

Whilst there were no idea Verdi voices in the cast, the sheer vividness and detail of the performances carried the day. The Opera North chorus was in great form, gibing a series of individual character sketches and sounding on form. In the pit, Garry Walker gave us lithe, fluent Verdi with a rhythmic alertness that reflect the work’s origins.

This was a performance that I could happily have seen again and again. There was so much detail in Elufowoju’s vision of the piece and the compelling way the performers responded to his ideas was profoundly rewarding.

Verdi: Rigoletto

Opera North at the Grand Theatre, Leeds

Greek Passion Review

Another Greek Passion Review

Tarmachan Ridge.

Winter has arrived.

Nottingham crit of Greek Passion

http://adrianspecs.blogspot.com/2019/11/cross-purposes-greek-passion-opera-north.html

Another crit ftom Manchester

http://www.mancunianmatters.co.uk/content/181178370-review-opera-norths-greek-passion-lowry-salford

Manchester Evening News Crit of Greek Passion

https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/whats-on/arts-culture-news/the-greek-passion-the-lowry-17275072

Opera Now Crit

Another good crit for Greek Passion

Opera Magazine Crit

The Greek Passion

Opera North at the Grand Theatre, Leeds, September 21

There can be few operas of greater conscience than Martinu's The Greek Passion, a work for today in every sense. Yet whether because it has fallen on deaf ears or hard hearts, it remains a rarity in the country that originally commissioned it—moreover, one that has been notably well disposed towards Czech music. Why? Its initial rejection by Covent Garden in the late 1950s may have had something to do with tensions over colonial Cyprus, but it has made only sporadic appearances since then and its return now in the Empire 2.0 era of tightening borders is not a moment too soon: Opera North's new staging, the first in this country in 20 years, shows how Martinu's final operatic masterpiece is perhaps the most moving and topically relevant opera of our time.

Based on Nikos Kazantzakis's novel of dispossession and displacement, its subject is exile, and all the elements of Martinu's own scattered life and diverse stylistic experimentation come together in the piece. The topic of forced migration confronting intolerance and bigotry clearly touched a composer who had spent his life in exile, the latter part of it enforced—his homeland was under totalitarian rule. That acutely personal feeling flares up most potently when Ales Brezina's reconstructed original version is used, as at Opera North. There is no contradiction between its intricate dramaturgy and simple honesty, at least not when they are reconciled so sensitively by the director Christopher Alden and conductor Garry Walker.

• Christopher Alden's new staging of'The Greek Passion'at Opera North, with Nicky Spence as Manolios

COPYRIGHT: This cutting is reproduced by Gorkana under licence from the NLA, CLA or other copyright owner. No further copying (including the printing of digital cuttings),

digital reproduction or forwarding is permitted except under license from the NLA, www.nla.co.uk (for newspapers) CLA, www.cla.co.uk (for books and magazines) or other copyright body.

Article Page 1 of 2 A23807 - 16

Media: Edition: Date: Page:

Opera {Front Cover}

Friday 1, November 2019 1461,1462

A French Review of Greek Passion

Opera North redonne sa chance (avec succès !) à The Greek Passion de Bohuslav Martinu

Nous nous l’étions (et vous l’avions) promis, au sortir d’une mémorable Aïda in loco en mai dernier, nous reviendrions bientôt à l’attachant Opera North de Leeds, pour cette rareté absolue que constitue The Greek Passion (La Passion grecque) de Bohuslav Martinu (mort en 1959). Cet ouvrage est en fait le dernier opus du compositeur tchèque, que lui avait inspiré la lecture du Christ recrucifié du célèbre romancier grec Nikos Kazantzakis. Il le rencontre à Antibes en 1954 et, fort de son accord, se met eu travail : en janvier 1956, la partition est achevée. Comme l’ouvrage doit être créé à la Royal Opera House de Londres (qui le lui a expressément commandé), le musicien écrit lui-même, en anglais, le livret. Mais des manigances à la tête de l’institution londonienne font finalement capoter le projet. L’œuvre ne sera créée qu’en 1961, dans une version allemande (remaniée) à l’Opéra de Zurich, et l’original anglais devra attendre 1999 pour être enfin porté à la scène, au Festival de Bregenz en l’occurrence.

A cause de sa rareté autant que de son pouvoir émotionnel (et de ses résonances actuelles), l’histoire mérite d’être ici narrée. Dans la Grèce de l’Asie mineure au début du XIXe siècle, le berger Manolios se voit confié le rôle du Christ dans le jeu de la Passion présenté par les gens du village de Lykovrissi. Peu à peu, le berger cesse de jouer et commence à incarner son personnage, à se substituer au Christ. La suite de l’histoire lui donnera l’occasion d’aller jusqu’au bout de son rôle et de son sacrifice. Le village est envahi par une troupe de paysans misérables chassés par les Turcs de leurs terres et cherchant désespérément un refuge. C’est à ce moment-là que la vie paisible et aisée de la commune tourne au drame et le sujet de l’opéra prend soudain des connotations universelles et aussi très actuelles... Après un premier élan de compassion et de miséricorde pour les réfugiés, les gens se détournent de ces intrus pauvres et incommodes qui meurent de faim et cherchent un terrain pour vivre. Les masques tombent et les villageois montrent leurs vrais visages, les personnages de l’Evangile se confondent avec les personnes réelles. Manolios s’oppose à ceux qui cherchent à chasser les misérables du village et cela provoque une explosion de haine contre lui. Le pope Grigoris l’excommunie de l’Eglise et Panait, homme qui campe le rôle de Judas, le tue. Le sacrifice est consommé et les réfugiés reprennent leur marche désespérée...

Comme le souligne le musicologue Isa Popelka, spécialiste des œuvres de Martinu : « Le Christ, allant pieds nus dans le monde et frappant en vain aux portes des riches, était pour Bohuslav Martinu non seulement une légende ancienne dans laquelle les innombrables déshérités projetaient leur sort ainsi que leurs espoirs toujours déçus, mais aussi un symbole dépassant largement le cadre du christianisme, une expression de l’éthique plébéienne consciente de la nécessité de compassion et de proximité humaine ainsi que de rapports harmonieux, non égoïstes et empreints de sympathie ». En Italie où, chaque jour, arrivent par centaines des réfugiés venus du continent africain pour fuir guerres et misère, une telle œuvre parle d’elle-même. Le metteur en scène new-yorkais Christopher Alden (à ne pas confondre avec son frère David Alden) choisit, à l’aide de son scénographe Charles Edwards et de sa costumière Doey Lüthi, de ne pas situer explicitement l’action - si ce n’est qu’elle est bien évidement transposée dans notre contemporanéité -, et recourt à la stylisation, au moyen d’un dispositif unique constitué d’une grande tribune (comme la réplique d’un théâtre grec), facilement manipulable, pour laisser le plateau vide quand l’action l’exige. C’est là que prend place le chœur, omniprésent ici, toujours placé frontalement au public, qu’il incarne le peuple des villageois ou celui des réfugiés. Ces derniers apparaissent avec des mannequins qu’ils tiennent dans leurs bras, symbole de leurs vies fragiles et aléatoires, et quand l’un d’entre eux meurt, le mannequin s’envole vers les cintres et reste alors suspendu en l’air… une image dérangeante qui vise à émouvoir et faire réfléchir le spectateur…

Dans le rôle de Manolios, le ténor écossais Nicky Spenceconvainc par l’intensité de son ténor puissant, qui ne craint pas de recourir jusqu’au cri pour éveiller les consciences. La jeune soprano polonaise Magdalena Molendowska impressionne plus encore : sa voix étale parcourt toute la tessiture de Katerina, avec une pugnacité qui ne perd jamais une once d’onctuosité. Le baryton anglais Stephen Gadd, de son côté, ne fait qu’une bouchée du rôle du riche et égoïste Pasteur Grigoris, auquel le compositeur réserve une musique belcantiste aux tournures assez convenues. Le reste de la (nombreuse) distribution se dépense sans compter, avec une mention pour John Savournin (Pasteur Fotis), l’indomptable défenseur des réfugiés, mais il faut également saluer le Panait brutal de Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts, ou encore la gracieuse Lenio de Lorna James, la fiancée abandonnée par Manolios. Quant au Chœur d’Opera North, il convainc autant par son engagement dramatique que par sa précision, notamment dans son saisissant Kyrie Eleison à la fin du II ! (voir la vidéo plus bas). Enfin, sous la baguette passionnée du chef d’orchestre britannique Garry Walker, l’Orchestre d’Opera North fait valoir toute la complexité d’une partition qui explore sentiments, conflits et croyances, avec un lyrisme envoûtant.

Une soirée magistrale… Vive Opera North !

Musical America

Musical America 26 September 2019

Mark Valencia

The Royal Opera aside, and passing respectfully over good work done by smaller outfits like English Touring Opera, most of the publicly supported British opera companies seem locked in a constant struggle with their finances and their identities. The Leeds-based Opera North, though, consistently fires on all cylinders and treats its north-of-England parish to exciting, imaginative programming and an extraordinary level of outreach work. Last December it was awarded Theatre Company of Sanctuary status in recognition of its efforts to give voice to the stories of refugees and asylum seekers. Which makes the choice of The Greek Passion to open ON’s new season seems almost inevitable.

Bohuslav Martinů’s 14th and final opera was the one he wrote twice. If you’re familiar with the 1981 Supraphon recording conducted by Charles Mackerras, which brought the 1959 revised score to wider attention, the 1957 original will sound like a different work. The composer wrote his own libretto based on the novel Christ Recrucified by Nikos Kasantzakis and the spine of it serves both versions. Yet there is a shock of differences between them.

It has grown common of late for productions of this opera to revert to the original version, using an edition that was painstakingly tracked down on the four winds by Aleš Březina, who then reconstructed it for performance at the 1999 Bregenz Festival. Now Opera North follows suit. However, this adherence to first principles is questionable for a number of reasons. First, as far as we know nobody pushed Martinů to rewrite it; the decision was entirely his own and was undertaken, one suspects, because he wanted to make the work more commercially attractive. (He had been stung by Covent Garden’s rejection of this English-language project and may have wanted to sugar the pill before offering it on to Zurich Opera.) Second, the original’s structure is fragmentary and uninvolving, almost Brechtian in its alienation and hamstrung by an extended coda that drains away the tension. The orchestral writing is vivid but stark, a savage sound picture only occasionally leavened by welcome relief from accordion or harp. Third, the rewritten version (‘Christ Recrucified Recrucified’, perhaps) has a melodic sweep and dramatic assurance that place it in the Bohemian lineage of Janáček and even Dvořák. Its structure is better balanced, its characterizations more convincingly achieved than in his initial draft. That’s how it Martinů chose to leave it when he succumbed to illness exactly 60 years ago.

In Březina’s program note he reminds us that Martinů campaigned to purge opera of “psychologizing dross”. Puzzling, then, that the company has hired New York’s king of psychological overlay, Christopher Alden, to direct its new production. While the result is handsome in execution its very austerity mitigates against a complete emotional engagement with such a highly charged story.

On Easter Sunday the elders of Lycovrissi, a small Greek village, gather to allocate roles in the following year’s Passion play. The shepherd Manolios is cast as Christ; but he takes his responsibilities too seriously for comfort and, to the consternation of the elders, reaches out to a group of refugees encamped nearby. It does not end well.

Tenor Nicky Spence, who sang Manolios, apologized for ill health on September 21, the night I attended, but there was no sign in his visceral performance that he was ailing. On the contrary, Britain’s leading Janáček tenor of today was vocally at home in a score that nourished his voice with choice cuts of ringing, near-heroic material. In acting terms he began the opera a lumbering man- child and ended it a martyr. If Spence had been allowed to interact more naturally with the other

characters he might have torn our souls, but such was the nature of Alden’s mannered staging that he was left to emote in a vacuum.

Designer Charles Edwards placed the drama on and around a towering yet mobile seating tier, seven rows in height, and used life-sized human plaster casts to represent the refugees. The flesh-and- blood bass John Savournin was their Priest and spokesperson. This staging device, in common with much of Alden’s concept, was effective for the storytelling but sterile as a depiction of human suffering.

Baritones Stephen Gadd as the Priest Grigoris and Jonathan Best as the wealthy Archon led the elders, while tenors Paul Nilon and Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts were prominent among the villagers chosen to enact the Passion. Among a predominantly male cast the two female principals were pivotal, and both Lorna James as Lenio and Magdalena Molendowska as Katerina were outstanding as the women in the shepherd’s life. With the excellent Chorus and Orchestra of Opera North on superb form under the company’s principal conductor-designate, Garry Walker, a Scottish musician whose Billy Budd in Leeds a year or two back confirmed him as a talent for years to come, this Greek Passion transcended the obstacles of text and staging to provide a vivid, intense musical experience.

Another Guardian review

Opera North is the first opera company in the UK to have been awarded the status of Theatre of Sanctuary, its involvement with those seeking refuge in the Leeds locality going far beyond any normal outreach programme. Staging Martinů’s rarely seen last opera, The Greek Passion (1957), whose subject is social displacement, therefore meant more than merely striving to put on a good show. Christopher Alden’s production, conducted by Garry Walker, the company’s music director designate, is certainly that: musically outstanding, striking in its depiction of Greek village life where simultaneous events – the staging of a passion play and the arrival of refugees – unsettle the community. Little wonder the performance of this lyrical, attractive but uneven piece (in an edition reconstructed by Aleš Brézina) had particular veracity.

Charles Edwards’s designs, a bank of retractable seating with white effigies to depict the faceless refugees, provided effective, simple imagery. Chorus and soloists – including Stephen Gadd, Paul Nilon, Magdalena Molendowska and, especially, John Savournin – excelled. The opera builds towards the shepherd Manolios’s soliloquy on charity. Chosen to play Christ, quiet at first, he struggles to match human instinct to this divine task until it bursts out of him, to tragic end. The tenor Nicky Spence, singing with open-hearted eloquence, made us think anew about the meaning of compassion.

And Another. The Times

A man in red robes carries a wooden cross on his back, bent double under its weight. Behind him, on raised seating, a white mannequin lies in a foetal position. These two potent symbols underpin Opera North’s new production of Martinu’s The Greek Passion, a parable about Christian charity and the plight of refugees. Staged with striking simplicity, the Czech composer’s final opera folds sacred teachings into a secular drama of strange power.

When a group of displaced people seek shelter in Lycovrissi, amid preparations for the traditional Passion play the villagers’ compassion is tested — and found wanting. The outcome is tragic. The play-within-a-play structure could overburden the plot, which is based on Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel Christ Recrucified, and you have to embrace its

moralising nature. Yet at its best The Greek Passion inspires deep reflection. The trick is, surely, to make the tale feel at once timeless and topical.

That’s what the director Christopher Alden and the set and lighting designer Charles Edwards achieve. In an era of mass migration it might have been tempting to milk the news. The programme booklet includes photos of the Calais Jungle, the US/Mexico border and Ukip’s “Breaking Point” billboard. On stage, however, John Savournin’s fervent Priest Fotis apart, the refugees are inanimate models; identical, dependent, dehumanised. The figures sit silently or are carried, the villagers singing their parts. It’s all the more impactful for avoiding politics.

Opera North opts for Ales Brezina’s reconstruction of the compelling original version, in English, just about getting away with updated asides about veganism and crisps. Yet there’s no doubt that Martinu’s music makes the heart weep and sing. Liturgical solemnity mingles with the colourful rhythms and inflections of folk music and it’s carried off with a theatrical flair that takes us from ominous timpani rolls to transcendent, tingling outpourings. The orchestra, under the music director designate Garry Walker, play with a suppleness and generosity that makes the score soar.

The cast puts in a strong ensemble performance. Nicky Spence is a sensitive, steadfast Manolios, the gentle shepherd subsumed by his acting role of Christ. Opposite him, Magdalena Molendowska’s Katerina is passionate and memorable. All around they find human weakness, whether it’s Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts’s tattooed Panait/Judas, Lorna James’s sparky Lenio or Stephen Gadd’s hypocritical Priest Grigoris. And the Chorus of Opera North is on fierce and fearless form, portraying the selfish callousness of a society that closes its doors on those in need.

And Another

https://theculturevulture.co.uk/cultures/music-opera-north-bohuslav-martinus-greek-greek-passion/

Another good crit.

https://www.thereviewshub.com/opera-norths-the-greek-passion-leeds-grand-theatre-leeds/

Another good review. Bachtrack

https://bachtrack.com/review-martinu-greek-passion-alden-spence-opera-north-leeds-september-2019

Review of Greek Passion From The Guardian.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/sep/16/the-greek-passion-review-martinu-grand-theatre-leeds

Review of Greek Passion from The Stage

huslav Martinu’s The Greek Passion may be more than 60 years old, but its contemporary relevance is stinging.

The Czech composer’s opera, presented by Opera North in its original 1957 version, tells the story of a group of refugees who flee to a Greek island where the villagers are performing a Passion Play for Easter. They face a hostile reception, but when the performers begin to take on aspects of their characters, passions are inflamed.

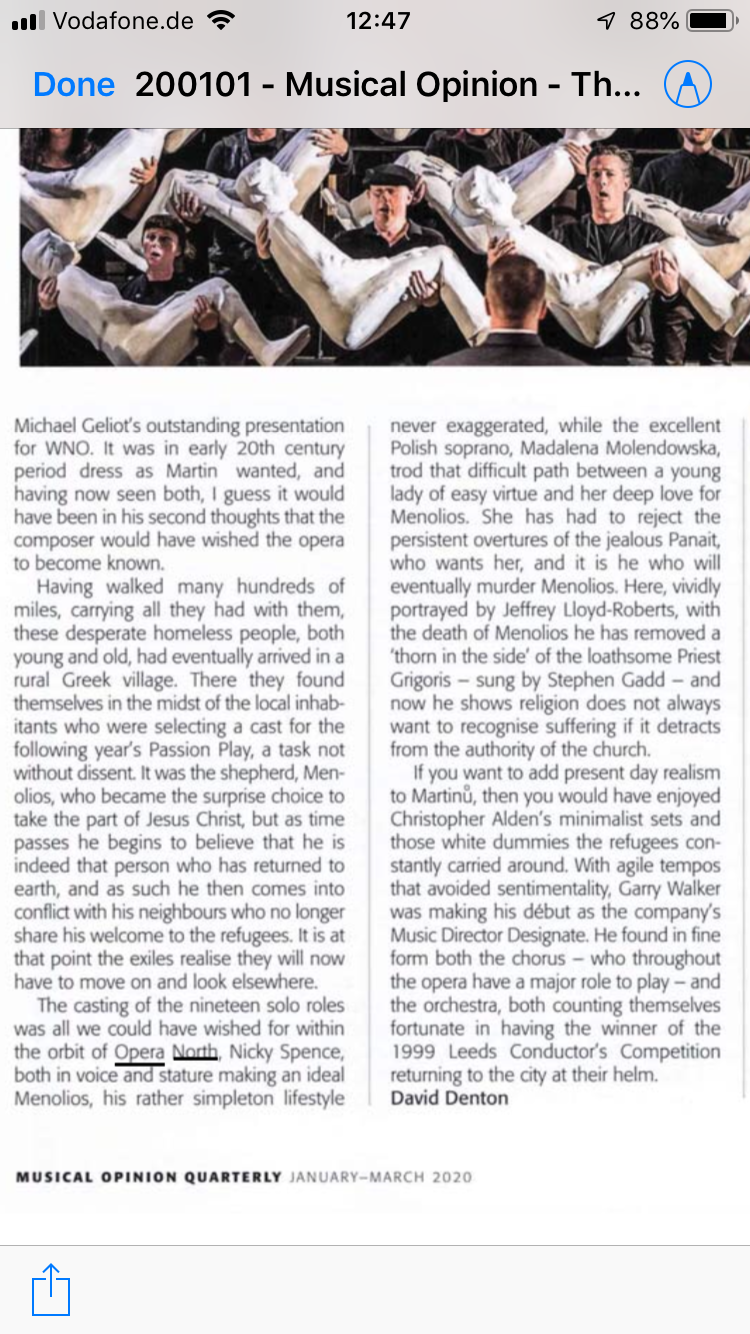

Charles Edwards’ set is both minimal and imposing, consisting of a huge bench-like steps structure, but it’s the representation of the refugees that really impresses. The Opera North chorus plays the roles of both the locals and the newcomers, holding stark white mannequins in their arms to give them a voice. When a refugee dies, the figure is hoisted up to the sky and the effect is eerie and unsettling.

Christopher Alden’s production makes some modern additions to Martinu’s music – there are touches of polka and folk to be heard, as well as a knee-slapping wedding

song with its own synchronised dance routine. It’s also necessarily dark. Nicky Spence is a tormented figure as Manolios, the ordinary villager struggling to be worthy to play Christ, while Magdalena Molendowska’s affecting soprano brings out the pain in her portrayal of the widow Katerina.

There are some updates to the text too – an exclamation of “bloody vegans!” receives the biggest laugh of the night. Yet this remains an opera with a message – the phrase “give us more of what you have too much of” hangs over the stage towards the end of both halves. Opera North has produced an accessible and powerful production that hits home hard.

Review of Greek Passion in the Sunday Times

Opera review: The Greek Passion, Opera North; Don Giovanni and Werther, Royal Opera

Martinu’s patchy Passion gets a powerful Opera North treatment

Holding pattern: the Opera North chorus in Martinu’s The Greek Passion

TRISTRAM KENTON

The Sunday Times, September 22 2019, 12:01am

In typically adventurous style, Opera North opened its 2019-20 season with a regional touring production of Bohuslav Martinu’s operatic swan song, The Greek Passion, based on Nikos Kazantzakis’s epic novel Christ Recrucified. This opera was famously rejected in 1957 by a subcommittee of the Covent Garden Opera Company, much to the consternation of its then music director, the great Czech conductor in exile Rafael Kubelik.

Kubelik clearly had an empathy not only with his compatriot’s score, but also with the subject matter: at Eastertide, village elders in Lycovrissi, Greece (under Ottoman rule in the novel), choose members of the community for leading roles in the annual Passion play. Their spokesman, the priest Grigoris, warns of the influx of a tribe of refugees seeking asylum from their Turkish oppressors. As the villagers take on characteristics of the parts they are playing, the shepherd Manolios, representing Christ, preaches charity and compassion towards the incomers. Grigoris denounces him as an apostate and incites the Judas character, Panait, to murder him. The refugees, realising they have lost their champion, move on.

Hugh Canning

It’s a powerful narrative, certainly, packed with interesting characters and biblical analogies — the widow Katerina, chosen to play Mary Magdalene and pursued by Panait/Judas, is physically attracted to Manolios — and it is splendidly performed in Leeds, conducted by Opera North’s music-director elect, Garry Walker, and simply staged by Christopher Alden, with enough political resonance to suggest analogies with our own time.

If there is a problem, as in 1957, it is with Martinu’s large-scale yet rarely unforgettable score. The prolific composer, adept in every genre, clearly struggled to find a distinctive “voice” in this cosmopolitan work, set to his own English libretto. For much of the evening, thanks to the heroic and touching central performance of Nicky Spence as Manolios, I thought fondly of Britten’s Peter Grimes, written a good decade earlier, but now a standard repertory piece, while The Greek Passion still hovers on the fringes.

Even so, this is one of ON’s great company shows, featuring a supporting cast that includes stalwart regulars such as Paul Nilon (Yannakos, the pedlar who plans to rob the refugees), Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts (Panait), Stephen Gadd (Grigoris) and John Savournin (the priest Fotis, the leader of the refugees). Magdalena Molendowska sings clear English words as a big-voiced Katerina. The chorus are so good, one wishes they had better music to sing.